I returned home from The Calgary Expo around 8:30 pm on Sunday, in good spirits but very tired. Shonna spent most of the day with me at the show, and it was fun to have her there. Even though she volunteered to help me tear down, I sent her home an hour before closing so she could beat the traffic.

With an established routine, I prefer to tear down alone and had the booth disassembled and loaded into the car in two hours. Shonna had homemade pizza waiting for me when I got home. She’s so sweet.

The week after Expo is almost as busy as the week before, unloading the car and stowing the booth hardware, taking post-show inventory, updating spreadsheets and paperwork, adding new subscribers to A Wilder View, and bookkeeping.

Add in the usual daily editorial cartoons, month-end invoicing and catching up on client emails, and it doesn’t slow down a little until midweek. And I still need to email those who inquired about pet portrait commissions.

People often joke that art-for-a-living isn’t work. I usually reply to those crass comments, “You’re absolutely right. I just draw and colour all day, and people throw money at me.”

From early prep to tear down, Expo went so smoothly that I kept waiting for something bad to happen. My booth location was ideal, my neighbours were friendly, and all the vendors I spoke with seemed to have a good show.

From early prep to tear down, Expo went so smoothly that I kept waiting for something bad to happen. My booth location was ideal, my neighbours were friendly, and all the vendors I spoke with seemed to have a good show.

Even the weather was good. It was a little windy and cold a couple of mornings, but walking back and forth to the hotel each day was comfortable. Considering it’s been snowing a few days this week, last week is nothing to complain about.

Though last year saw the best sales I’ve had at this show, this year was a very close second. Considering the current economy, I’m very pleased.

With the BMO Centre renovations and expansion nearing completion, the 2025 Expo will see everything together in a brand-new state-of-the-art convention centre next door rather than spread out over several halls and two buildings. It should be an exciting year.

I always come away from this show inspired to draw and paint, with an overwhelming gratitude for those who allow me to keep doing it. Like most artists, I’m an introvert who spends most of my time alone with my work, so when I meet people who enjoy it, it refills the creative tank.

I always come away from this show inspired to draw and paint, with an overwhelming gratitude for those who allow me to keep doing it. Like most artists, I’m an introvert who spends most of my time alone with my work, so when I meet people who enjoy it, it refills the creative tank.

During the first two hours on Thursday, I saw many regulars flood my booth. It was chaos, it was bedlam, it was awesome. The only downside was that these were all people I wanted to spend extra time with, but they all showed up at once. I had the best Thursday sales I’ve ever had, and most of those were from longtime collectors and subscribers to A Wilder View.

During the first two hours on Thursday, I saw many regulars flood my booth. It was chaos, it was bedlam, it was awesome. The only downside was that these were all people I wanted to spend extra time with, but they all showed up at once. I had the best Thursday sales I’ve ever had, and most of those were from longtime collectors and subscribers to A Wilder View.

Paintings, Products and Prints

Postcard sets had a slow start on Thursday, but I figured out by Friday how to display them better and talk about them more. Stuff doesn’t sell itself; you must engage with people and let them know what’s available, especially if it’s something new. Magnets, stickers, and coasters continue to be popular items.

As I’ve written before, Expo is a proving ground for determining which paintings make for popular prints. While all the new paintings were well received, Highland Cow, Raven on White and Spa Day were top sellers.

As I’ve written before, Expo is a proving ground for determining which paintings make for popular prints. While all the new paintings were well received, Highland Cow, Raven on White and Spa Day were top sellers.

Because of early feedback, I brought a lot of the Highland Cow with me, but I still sold out by Saturday morning. I have never sold that many of one print at any show. Who knew?

Process

The best part of this show is talking with people who collect my work, many of whom I now consider friends. Their feedback gives me plenty to think about, especially when it comes to what I share in A Wilder View.

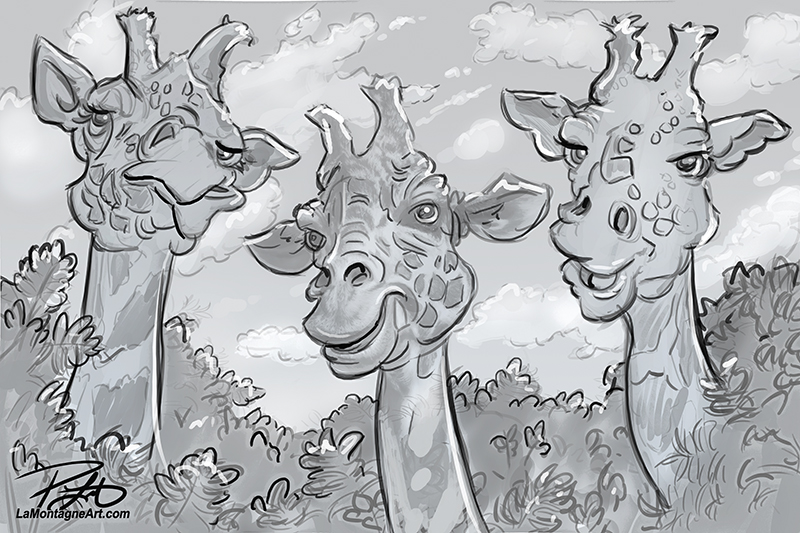

One collector and friend told me that he likes my Long Neck Buds giraffes piece because I shared the different stages of the painting from start to finish. He said it made him feel part of the process. I only did that because the image was so involved and took longer than most paintings, and I still wanted to send out regular emails.

One collector and friend told me that he likes my Long Neck Buds giraffes piece because I shared the different stages of the painting from start to finish. He said it made him feel part of the process. I only did that because the image was so involved and took longer than most paintings, and I still wanted to send out regular emails.

When I asked some other longtime Expo subscribers for their take on it, everyone agreed.

I had thought half-finished work might be boring, and the perfectionist part of me is reluctant to share the unpolished stages of work in progress. But from now on, you’ll see a lot more of my painting process.

I had thought half-finished work might be boring, and the perfectionist part of me is reluctant to share the unpolished stages of work in progress. But from now on, you’ll see a lot more of my painting process.

Thanks again for that feedback, Sheldon.

Puzzles

With only two Sea Turtle puzzles in stock, I left them off the Expo price list and didn’t put them out because it might look a little sad. But I brought them along just in case.

When two people asked about puzzles, they liked and bought them. I’m now sold out and pleased with that whole venture. Thanks again to all who pre-ordered and bought the first round of puzzles last year and everyone who bought them online, at the Banff Christmas Markets and Calgary Expos.

I’m working on five different paintings right now, a few that feature multiple animals in the scene, and I aim to include those on future puzzles later this summer, 1000-piece options many of you have been asking for.

I’m working on five different paintings right now, a few that feature multiple animals in the scene, and I aim to include those on future puzzles later this summer, 1000-piece options many of you have been asking for.

What’s Next?

With Expo behind me, I’m focusing on paintings in progress, future pieces on the horizon and ongoing projects. Once this round of spring snow ends, I’ll deliver a large print and sticker order to Discovery Wildlife Park as they open for the season this week.

I hope to deliver another print and sticker order to the Calgary Zoo soon, allowing me to take some spring reference photos for future paintings. I didn’t visit the Alberta Birds of Prey Foundation in Coaldale last year. I plan to make up for that later this month as I take a trip south to see some eagles, owls, and hawks at their newly renovated and improved facility.

And, of course, I will kick myself in the hindquarters to replace talking about the book with working on the book…dammit. Some of my collectors don’t have any wall space left! They’ve waited long enough.

Whether you added to your collection this year at Expo or just visited me for a chat, thanks for being there. You remind me that my happy-looking critters matter to so many of you, which means more to me than you know.

Until next time.

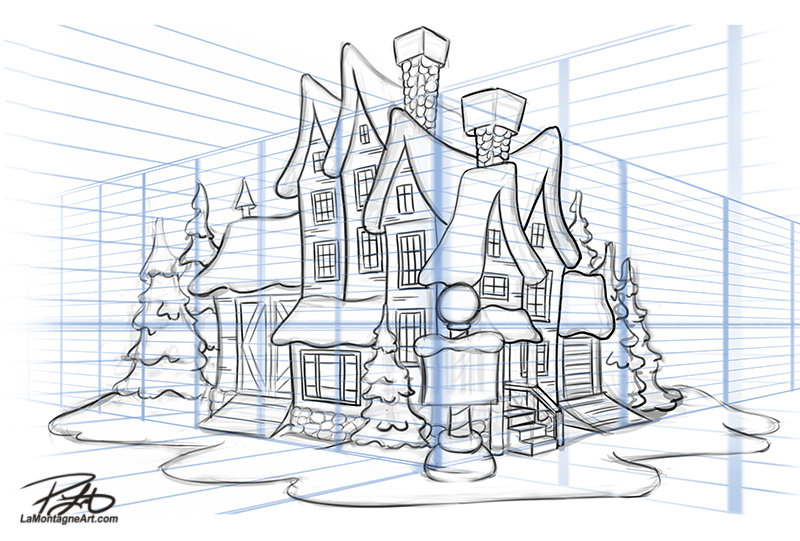

Then I’ll drop the opacity of the sketch layer, so it’s very faint and create cleaner black lines on the layer above. I call this an Ink layer, even though there’s no ink involved.

Then I’ll drop the opacity of the sketch layer, so it’s very faint and create cleaner black lines on the layer above. I call this an Ink layer, even though there’s no ink involved. I’ll delete the sketch, create a new layer beneath the ink layer and fill in sections of flat colour on different layers. This helps me establish a base colour for separate pieces and select certain painting sections easily.

I’ll delete the sketch, create a new layer beneath the ink layer and fill in sections of flat colour on different layers. This helps me establish a base colour for separate pieces and select certain painting sections easily. Finally, I’ll create a painted background, add talk bubbles, my text and signature, and save different formats to send to my newspaper clients across Canada.

Finally, I’ll create a painted background, add talk bubbles, my text and signature, and save different formats to send to my newspaper clients across Canada. The painting process I use for my whimsical wildlife and portraits of people is more complicated because each painting takes many hours to complete and involves a lot of fine detail. But the tools are the same. Many artists have asked me about my painting brushes over the years, and they’re surprised that they’re not complicated. Just like in traditional art, it isn’t the brush; it’s the person wielding it.

The painting process I use for my whimsical wildlife and portraits of people is more complicated because each painting takes many hours to complete and involves a lot of fine detail. But the tools are the same. Many artists have asked me about my painting brushes over the years, and they’re surprised that they’re not complicated. Just like in traditional art, it isn’t the brush; it’s the person wielding it.

____

____